FOR YEARS, the American food story has been primarily told as a white food story. The Netflix series “High on the Hog: How African American Food Transformed America” seeks to change that.

Much of the history and culture presented in the four-episode docuseries, which starts streaming May 26, may be new to some viewers. But the seminal book on which the show is based, “High on the Hog: A Culinary Journey from Africa to America,” by the influential food historian Jessica B. Harris, was published in 2011. “I think that it was time for this particular story to be told in this particular way,” Dr. Harris said of the show. “There are so many people now writing about the food of the African diaspora, writing about the food of African Americans, and there’s a need for this kind of storytelling.”

“

It’s not just soul food. I think it’s important for people to see that Black cuisine permeates everywhere.

”

Executive producer Fabienne Toback talked about the project’s sweeping historical scope. “There’s so many struggles that Black Americans are going through today, and that we have been going through for the past 400-plus years,” she said. “Any opportunity where we can acknowledge our own contribution for the wonderful things that there are in this country—including something as American as mac and cheese—I think it’s wonderful.”

Share your experience with this recipe. Did you make any adaptations? How did you serve it? Join the conversation below.

Ms. Toback and fellow executive producer Karis Jagger are both Black women and food enthusiasts. After optioning the book, they brought on Black directors, including Roger Ross Williams. Their goal: to amplify Dr. Harris’s life’s work and shine a light on a rich legacy of culinary ingenuity that continues to evolve in Black homes, kitchens and restaurants, in Africa and the U.S. “We were looking for something meaningful, and this was that story,” said Ms. Jagger.

The show’s host, Stephen Satterfield, is already well known in the world of food media. He founded the multimedia company Whetstone and the culinary journal of the same name; he also trained as a chef and spent over a decade working as a sommelier in fine-dining restaurants. Mr. Satterfield acknowledged the work of Dr. Harris as an inspiration for his own career and the impetus to take on the role of host for this series. “Seeing the rigor of her scholarship and the quality of her writing and storytelling was so affirmative for me to absorb as a student, but also to understand as a benchmark for the work that I wanted to try to make in the world.”

In episode one, Mr. Satterfield and Dr. Harris travel around Benin. They receive an education on rice and okra at a local market; eat amiwo, a savory dish of corn flour and tomato served with braised chicken, at the restaurant Saveurs du Benin in the city of Cotonou; and come face to face with landmarks of a traumatic history of enslavement.

In subsequent episodes Mr. Satterfield returns stateside. He invites us along to examine the African expertise and forced labor that built the Carolinas’ lucrative rice industry. With him, we learn about “Hercules,” a chef enslaved by George Washington’s family, and the role of African Americans in the oyster trade. In Texas he visits the kitchen of baker and photographer Jerelle Guy for a meditation on innovation and emancipation; on horseback, no less, he uncovers a long legacy of Black cowboys unknown to most Americans.

As Mr. Satterfield introduces us to friends and colleagues such as farmer and cook Gabrielle Eitienne (see her recipe for smoky burnt-sugar beet cornbread, at left), oysterman Benjamin “Moody” Harney and Philadelphia chef Omar Tate, it becomes clear that other young Black makers and leaders are taking up the baton held out by Dr. Harris’s generation, and, like their ancestors, they are finding a route to freedom through food.

“It’s about getting away from the monolithic view of what Black food is,” said Ms. Tobak. “It’s not just soul food. I think it’s important for people to see that Black cuisine permeates everywhere.” And that’s only the starting point of this series, in Mr. Satterfield’s view. “It’s so important to understand the outside influence and impact of the African American and African diaspora’s hand, not just in the cuisine, but in the culture around the cuisine,” he said. “All of the things that we so enjoy as customary so-called ‘American Life’…That dream or framework as we understand it would not be possible without Black people.”

To explore and search through all our recipes, check out the new WSJ Recipes page.

Copyright ©2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8

24World Media does not take any responsibility of the information you see on this page. The content this page contains is from independent third-party content provider. If you have any concerns regarding the content, please free to write us here: contact@24worldmedia.com

5 Characteristics of Truth and Consequences in NM

How To Make Your Wedding More Accessible

Ensure Large-Format Printing Success With These Tips

4 Reasons To Consider an Artificial Lawn

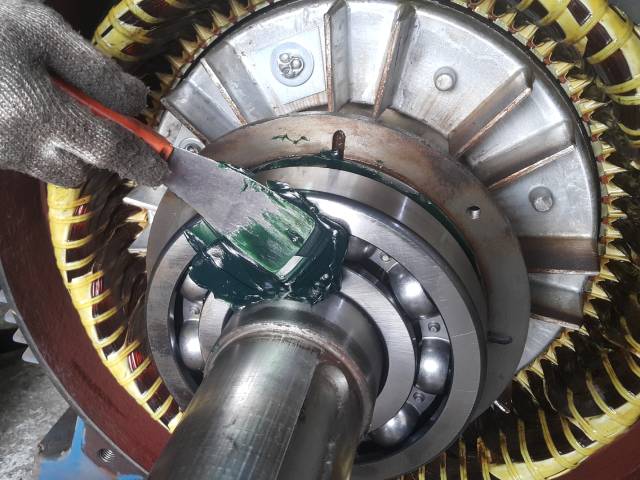

The Importance of Industrial Bearings in Manufacturing

5 Tips for Getting Your First Product Out the Door

Most Popular Metal Alloys for Industrial Applications

5 Errors To Avoid in Your Pharmaceutical Clinical Trial

Ways You Can Make Your Mining Operation Cleaner

Tips for Starting a New Part of Your Life

Easy Ways To Beautify Your Home’s Exterior

Tips for Staying Competitive in the Manufacturing Industry