IN THE LATE 1990s when I was coming of age, Victoria’s Secret loomed large. The company’s notoriously sexy catalog, filled with perfect-seeming “Angels” like Heidi Klum, Tyra Banks, Stephanie Seymour and Karen Mulder, was the focus of jokes on sitcoms and among the kids in my class. My friends and I would travel in giggling, anxious packs to the store’s pink-and-marble emporiums at the mall, shopping for satin pushup Miracle Bras, sheer shiny Angel Bras and saccharine body sprays that smelled like…Victoria’s Secret stores. During that time, stock in Victoria’s Secret’s parent company

soared, making its owner

Leslie Wexner

a billionaire.

Roy Larson Raymond had started the chain in 1977, after finding himself uncomfortable buying his wife lingerie at a department store. But I recall feeling distinctly out of my element at his resulting retail venture, and many women I spoke to agreed. Marissa Vosper, the co-founder of underwear brand Negative, remembered, “At the time, I think many women default-shopped at Victoria’s Secret and would [later] tell us how embarrassed they were to be seen with a shopping bag, and so would literally hide the product in their handbag.”

Today, Victoria’s Secret is attempting to find its footing amid changing beauty standards and declining market share. Last year Mr. Wexner stepped down as CEO and chairman of L Brands amidst investigation into his ties with the late, disgraced financier Jeffrey Epstein. Through a spokesperson Mr. Wexner declined to comment. The company has tried to modernize its image by ditching its annual Angels fashion show and hiring a wider range of models. A spokesperson for L Brands emphasized new leadership hires and a focus on the digital business. In a February earnings call, CEO

Martin Waters

said, “I couldn’t be more delighted to be leading the work to refresh the brand positioning to make it more relevant, to make it more inclusive, to make it more consistent with the attitude and lifestyle of the modern woman.” He also said, “We’re moving from what men want to what women want.”

In the Goldilocks game of underwear shopping, alternatives to Victoria’s Secret have included fancy, frilly options like Kiki de Montparnasse and Agent Provocateur, as well as cheap basics by Aerie and GapBody. But now women young and old are seeking new underwear brands they can identify with more fully. They demand comfort as well as sexiness and structure, inclusive sizing and non-objectifying advertising imagery featuring a diverse group of models. And increasingly, direct-to-consumer underwear companies, many of them founded by women, are answering that call. Within the past 10 years, we’ve witnessed the rise of such brands as ThirdLove, Negative, Cuup, Skims, Kit Undergarments, Savage X Fenty, True & Co. and Parade. Call them the anti-Victoria’s Secrets.

Christina Yannello, a beauty influencer and real-estate agent in New York, told me,”I grew up with Victoria’s Secret Pink and now I’m 22 and I would much rather buy a more positive brand.” To her, that means pieces from Cuup and Parade, such as a brown mesh unlined Cuup bra. She continued, “I have learned to love my curves, I have learned to love my body, but growing up, seeing all of these perfect women being advertised, was really hard.”

“In many ways, the arc of American femininity has been tied to the American underwear story,” posited Cami Téllez, a 23-year-old entrepreneur who dropped out of Columbia University to launch Parade in 2019. Her brand, a line of brightly colored basics that prides itself on using mostly recycled fabrics, recently raised $10 million in Series A funding and has sold over a million pairs of underwear.

As Gen Z and millennial consumers became more eco-conscious and questioning of gender and beauty scripts, they in turn needed new intimates. ”I saw an opportunity for an entirely new narrative within the underwear space,” explained Ms. Téllez. Like many DTC companies, Parade champions values such as sustainability and self-expression over the top-down approach of yesteryear, which often included expensive fashion shows and big flagship stores.

Another key value for Parade is affordability. As someone who had taken on student loan debt, Ms. Téllez is aware that price point can be crucial when weighing underwear choices. Most Parade underwear costs less than $10, which puts it in the sweet spot for young women on a budget. For the previous generation, women’s lingerie was often marketed as something that men would buy for them: A 1997 Victoria’s Secret Christmas commercial showing the Angels cavorting with Santa was stamped with the toll-free number “1-800-HER-GIFT.”

While Parade is grabbing headlines at the moment, it joins other brands that have been innovating in this market for years now. Negative, launched in 2014 by Ms. Vosper and Lauren Schwab, and Cuup, started in 2018 by Abby Morgan, Kearnon O’Molony, Lauren Cohan and Chrisden Ferrari, offer pieces that are a bit more pricey and sophisticated-looking than the Parade basics. Perhaps because of my demographic (30s, always online), both serve me incessant ads on Instagram. The designs rely on neutral colors—browns, grays, pale pink—and the kind of algorithm-informed baseline of good taste which has evolved to include acknowledgement of curvy bodies with different skin tones.

In fact, I’ve heard these types of brands referred to colloquially as “Instagram bra companies” because of their reliance on social-media targeted ads. But their marketing strategies go deeper. Cuup, for example, does have some older customers who are not necessarily digitally savvy, according to co-founder Abby Morgan. For that woman, Cuup uses direct mail, retail pop-ups and office fittings. It also does promotions with a breed of influencers who are more or less offline but still considered “thought leaders in certain communities”—a PTA coordinator, for example, or a nurse. These women might get a promo code, some product, and the chance to tell their story on Cuup’s website.

Mae Karwowski, a founder of the influencer-marketing firm Obviously, sees these brands’ marketing as “the antithesis of the Victoria’s Secret strategy.” She went on that while the status quo was once about trying to attain a supermodel figure by working out twice a day, these new companies are communicating a message that she summed up as: “We’re totally on the other end of the spectrum here…You don’t need to be a supermodel, actually we’re swinging in the other direction, we want real people and we want you to represent us.”

However even as underwear companies strive to be more inclusive, not everyone sees themselves represented in the product or the advertising. Megan Taylor, 21, a student in New York, bought a sheer Cuup bra and posted a photo of herself wearing it to Instagram. But she was then discouraged by the fact that the company didn’t carry her roommate’s larger size. Said Ms. Taylor, “I know I live in a privileged body, and that I can fit into the majority of standard sizing, but it’s not fair to everybody, which is not how it should be.” Ms. Morgan of Cuup said that the brand is working on expanding its size run.

Simone Mariposa, a Los Angeles influencer who calls herself “superfat,” said that while these brands were moving in the right direction, she would like to see larger women represented “in a sexy light,” not just wearing basic underwear. She said, “There needs to be more legit size diversity, not just in what’s manufactured but what is advertised. I know if I see a body that looks like mine, I’m going to feel like, ‘OK, this brand gets it.’”

Copyright ©2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8

24World Media does not take any responsibility of the information you see on this page. The content this page contains is from independent third-party content provider. If you have any concerns regarding the content, please free to write us here: contact@24worldmedia.com

A Brief Look at the History of Telematics and Vehicles

Tips for Helping Your Students Learn More Efficiently

How To Diagnose Common Diesel Engine Problems Like a Pro

4 Common Myths About Wildland Firefighting Debunked

Is It Possible To Modernize Off-Grid Living?

4 Advantages of Owning Your Own Dump Truck

5 Characteristics of Truth and Consequences in NM

How To Make Your Wedding More Accessible

Ensure Large-Format Printing Success With These Tips

4 Reasons To Consider an Artificial Lawn

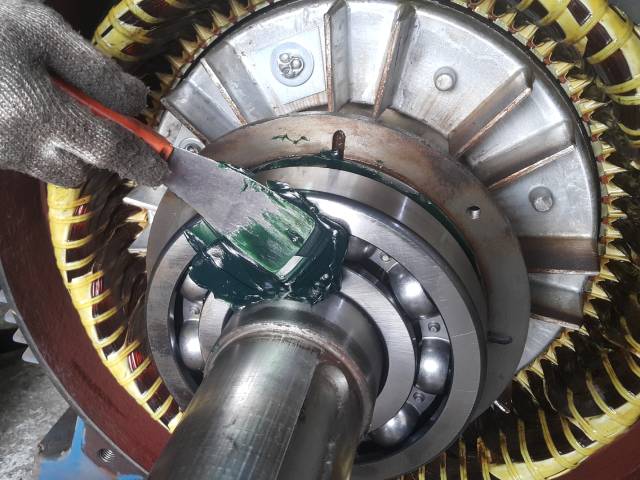

The Importance of Industrial Bearings in Manufacturing

5 Tips for Getting Your First Product Out the Door