MONTREAL — Forgive me, please, for repeating myself, as people of a certain age often do. I’ve written columns before on major anniversaries of the assassination of John F. Kennedy. But I have just left a remarkable sculpture exhibit in the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts and found myself walking down Avenue du President-Kennedy, remembering the whole awful episode, 60 years ago this week: the memory that won’t go away, the memory that, in defiance of human experience, somehow gets fresher every year.

The sculpture exhibit is a retrospective on the work of Marisol, the Venezuelan-American sculptor who, in small wooden figures sitting below a massive carving of John F. Kennedy Jr. — the 3-year-old in full salute, the way the military men once saluted his fallen father — triggered a flood of memories, none of them nostalgic.

If you were alive on Nov. 22, 1963 — and, given the demographics of newspaper readership, there’s a good chance you were — you don’t have to be reminded of what happened that afternoon in Dallas. Mere words will be sufficient: Tarmac greeting. Pink dress. Motorcade. Shots. Texas Book Depository. Clint Hill. Parkland Hospital. J.D. Tippit. Lee Harvey Oswald. Air Force One. Sarah Hughes. Lyndon Johnson: I will do my best… I ask for your help, and God’s.

So much has happened since then — more assassinations; the civil rights, women’s, and gay rights movements; a superpower bogged down in places that seemed peripheral in 1963, like Vietnam, Iraq, above all Afghanistan; massive transformations in commerce, technology, manners. And yet that terrible day retains its awesome power. Authors have written that football teams preparing for weekend games took off Friday morning in one country and landed, Friday afternoon, in another. You don’t have to have been on an airplane — a DC-8, for example, a popular airliner at the time — to feel that way.

Two stories from two of my closest friends, both in their 80s, demonstrate the effectiveness of sports as a metaphor.

Matt Storin, later the editor of The Boston Globe, was Notre Dame’s football manager. With Iowa on its schedule for the following day, the team left South Bend, Ind., for its flight to Cedar Rapids. “Ordinarily football players walking through an airport attract attention,” he recalled. “Nobody looked up. Everybody was watching the body of the president being returned to Andrews Air Force Base.”

Jack DeGange was the Yale football beat writer for the old New Haven Journal-Courier. It was the day before the Harvard-Yale game, and the universities’ freshman teams were preparing to play at DeWitt Cuyler Field, now named in memory of Clint Frank. On the sidelines, he remembers vividly, Bob Kiphuth, Yale’s legendary swimming coach, stood by his car, door open, radio turned full blast to the news. When Yale’s varsity took to the Yale Bowl turf for practice, the Yale football manager, Bill Schaffer, told coach John Pont the game was postponed.

So much more would be postponed; some things were canceled. You might say the great age of America itself was canceled that afternoon.

“That day,” Mark Migotti, the chairman of the philosophy department at the University of Calgary, told me, “seemed to be the cutting off of the head of Camelot.”

Of course, the slaying of a young president in a country at peace globally, if not exactly at home, is a tragedy that deserves remembrance. But there’s more to it than that.

In a broader way, that day represented the collapse of American naivete and idealism. We didn’t realize until Kennedy was dead just how much his youth, enthusiasm and vigor — he pronounced it vigah, though for him it was a painful version, riddled as he was with aches and illness — captivated us, and the world. Except for flurries with (on the right) Ronald Reagan and (on the left) Barack Obama, we’ve felt more captive than captivated by our leaders since then.

Assassinations have changed history. The movement from Abraham Lincoln to Andrew Johnson in 1865 signaled the end of hope and in many ways the beginning of despair. The movement from William McKinley to Theodore Roosevelt in 1901 began a dramatic transformation in the Republican Party from a conception of an unabashedly pro-business government to one of reformist activism and intervention.

The Kennedy assassination, however, was an exception. “Let us continue,” Johnson said in a vow to redeem the Kennedy policies, and did. He won the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that were in Kennedy’s portfolio of proposals but beyond his political reach.

Try as he might, skilled as he was, LBJ ultimately was unable simply to “continue.” In an image the ranch horseman might have appreciated, history moved from easy canter to a gallop of despair.

That November 1963 day was a jolt for a country that, just 18 years after the conclusion of World War II, still was in a “post-war” reverie. Yes, there was the Cold War, with the triumph of the Berlin Airlift and, 13 months before the assassination, the terror of the Cuban Missile Crisis. But until that Friday, Americans hadn’t experienced tragedy in their public life since the death of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. They were living in a warm bath of security, and part of it — here Dwight Eisenhower deserves some credit — was a sense of security about their leaders.

Americans would not experience another shared tragedy like the Kennedy assassination for 38 years, when terrorists attacked Manhattan and Washington, D.C.

In Montreal, a young man stands at attention in a museum display. Those of us who were young then have never quite been at ease. Which is why Daniel Patrick Moynihan, later a senator, had an answer when the columnist Mary McGrory said, “We’ll never laugh again.” His response: “Mary, we will laugh again. It’s just that we will never be young again.”

And so, in the year 2061, if columnists are still permitted a moment of recollection, writers now 32 years old may share thoughts much like these about their 60th anniversary memories of 9/11. I won’t be around to read them. You may be. So — please — give those columnists a few minutes’ time to explain the moment that means the most to them. Those future columnists might find meaning, as I do, in the immortal opening line of L.P. Hartley’s “The Go-Between”: “The past is a foreign country. They do things differently there.”

A Swampscott High School Class of 1972 member, David M. Shribman is the Pulitzer Prize-winning former executive editor of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

24World Media does not take any responsibility of the information you see on this page. The content this page contains is from independent third-party content provider. If you have any concerns regarding the content, please free to write us here: contact@24worldmedia.com

A Brief Look at the History of Telematics and Vehicles

Tips for Helping Your Students Learn More Efficiently

How To Diagnose Common Diesel Engine Problems Like a Pro

4 Common Myths About Wildland Firefighting Debunked

Is It Possible To Modernize Off-Grid Living?

4 Advantages of Owning Your Own Dump Truck

5 Characteristics of Truth and Consequences in NM

How To Make Your Wedding More Accessible

Ensure Large-Format Printing Success With These Tips

4 Reasons To Consider an Artificial Lawn

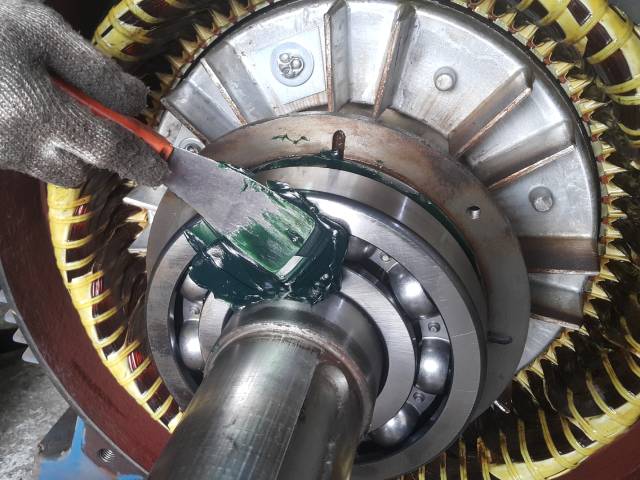

The Importance of Industrial Bearings in Manufacturing

5 Tips for Getting Your First Product Out the Door